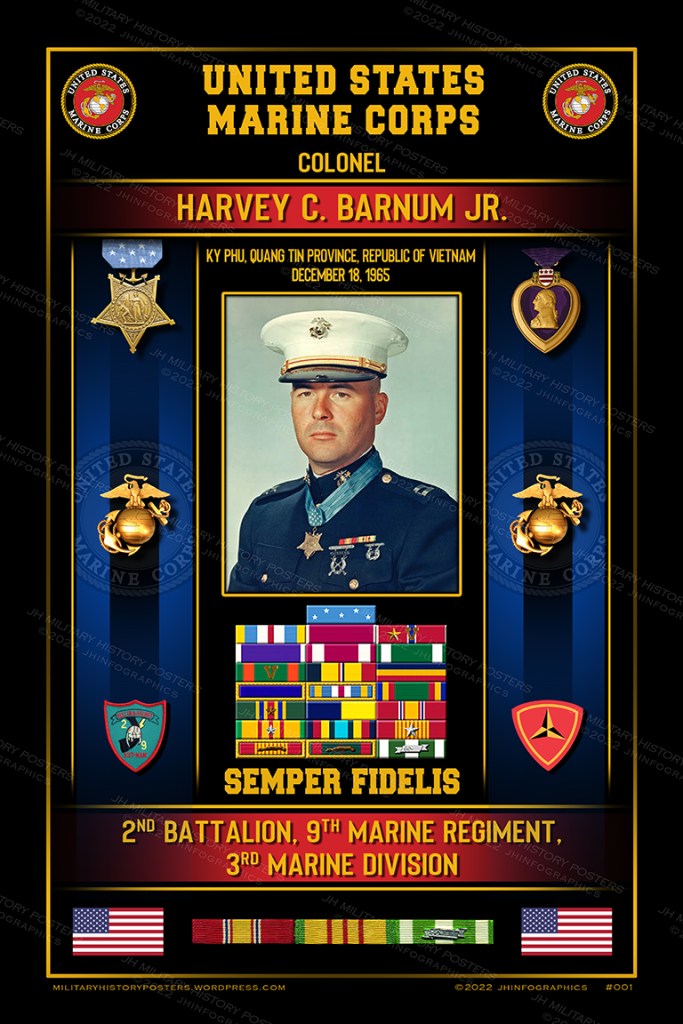

COLONEL HARVEY C. BARNUM JR.

On December 18, Barnum’s battalion was marching to the village of Ky Phu. If only they’d known that Viet Cong fighters were lying in wait. The Viet Cong allowed part of the battalion to pass by before striking. They hoped to divide the Americans, leaving some of them isolated and vulnerable.

Unfortunately, Barnum’s company was bringing up the rear, so they were the ones who got isolated and cut off from their comrades. Worse, the initial attack mortally wounded the company’s commander, Paul Gormley. The radio operator was also killed.

“We were taken under intense fire,” Barnum later recalled. “It was the first time I had ever been shot at. So, I hit the deck. And when I looked up from underneath my helmet, all these young Marines were looking at me like ‘Lieutenant, what are going to do?’”

Barnum leapt into action. He pulled the dying Gormley back into cover. He’d risked his life to do it, but to no avail. Gormley died within minutes. Barnum rushed out again, this time to retrieve the company’s radio.

Because of Barnum, some wounded men were evacuated first. He reorganized the men, and he used the radio to direct aerial attacks. These efforts cleared a landing area for transport helicopters.

“Harvey was on the radio himself,” one witness later said, “and called for the chopper to land on a small hill near the wounded men. The pilot responded that the hill was ‘too hot to land in,’ or words to that effect. Whereupon, Barney, with the radio on his back, walked out onto the hill and said to the pilot, ‘Look down here where I am standing. If I can stand here, by God, you can land here!’ And the chopper did, although the hill in fact was under fire at the time. And Barney got his wounded out.”

Barnum’s company had a big problem: Darkness was falling. They needed to get back to the village to join everyone else. And fast. But no one could help. “You know, skipper, you gotta come out,” Barnum was told. “We can’t come get you. We’re in our own fight in the village. You’re on your own. If you don’t come out, you’re in there by yourself tonight.”

Barnum was low on ammunition and he was outnumbered, but it didn’t matter. He had to act. He urged his men to make one last run toward the village. The unexpected run, into the open, took the enemy by surprise.

“It is the worst feeling in the world to charge across fire-swept ground,” he later said. “You’re right in the open. But I told everyone, Once we start, guys, there’s no stopping. . . . And when it came my turn, I never ran so damn fast in my life!”

Amazingly, Barnum’s company made it to the camp—and they immediately helped with its defense.

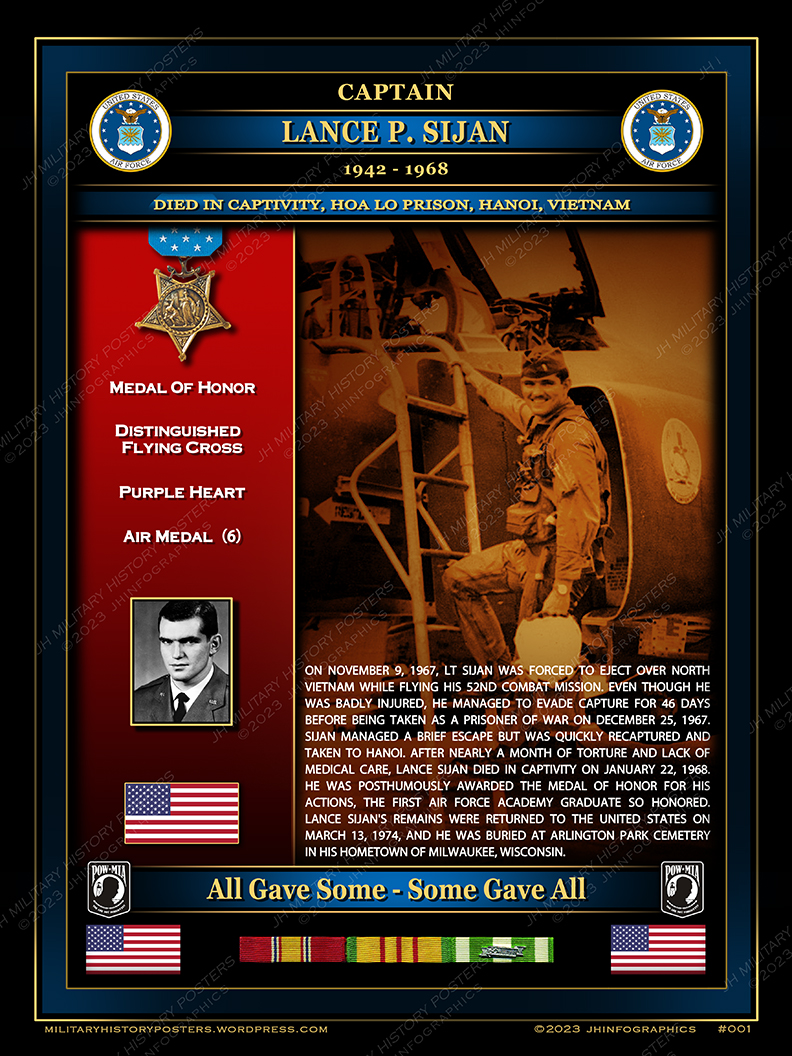

CAPTAIN LANCE P. SIJAN

CSM Adkins was deployed to Vietnam for three non-consecutive tours while in the Special Forces: the first was for six months, beginning in February 1963. The second tour started in September 1965 and lasted for a year. The last one was from January 1971 until December that same year.

His second tour in Vietnam was when the most remarkable actions would happen. On March 9, 1966, then-Sergeant First Class Bennie Adkins was at Camp A Shau, serving as an Intelligence Sergeant with Detachment A-102, 5th Special Forces Group, 1st Special Forces. Their early morning hours were welcomed by a large force of North Vietnamese soldiers attacking them. Sergeant Adkins did not waste a second and rushed amidst the hail of enemy fire to man a mortar position to defend the camp. The enemy mortars hit him on a few occasions, and he incurred wounds from them. But Adkins was undeterred. He continued fighting. When he heard that several soldiers were wounded, he left his position and had another soldier man it so he could run through the mortar rounds and onto his wounded comrades’ position. Without hesitation, he dragged several of them to safety. When the hostilities subsided, Adkins exposed himself to the enemy snipers so he could carry the wounded soldiers to a safer area.

He exposed himself to enemy bullets even more while transporting a wounded man to an airstrip, and if all these were not enough yet, members of the Civilian Irregular Defense Group who had defected to fight with the Viet Cong began firing at them, too, with their heavy small arms. When a resupply air drop landed outside of the camp perimeter, Sergeant First Class Adkins, again, moved outside of the camp walls to retrieve the much needed supplies. During the early morning hours of March 10, 1966 enemy forces launched their main attack and within two hours, Sergeant First Class Adkins was the only man firing a mortar weapon. When all mortar rounds were expended, Sergeant First Class Adkins began placing effective recoilless rifle fire upon enemy positions.

Despite receiving additional wounds from enemy rounds exploding on his position, Sergeant First Class Adkins fought off intense waves of attacking Viet Cong. Sergeant First Class Adkins eliminated numerous insurgents with small arms fire after withdrawing to a communications bunker with several soldiers. Running extremely low on ammunition, he returned to the mortar pit, gathered vital ammunition and ran through intense fire back to the bunker. After being ordered to evacuate the camp, Sergeant First Class Adkins and a small group of soldiers destroyed all signal equipment and classified documents, dug their way out of the rear of the bunker and fought their way out of the camp. While carrying a wounded soldier to the extraction point he learned that the last helicopter had already departed. Sergeant First Class Adkins led the group while evading the enemy until they were rescued by helicopter on March 12, 1966.

COLONEL ROGER H.C. DONLON

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while defending a U.S. military installation against a fierce attack by hostile forces. Capt. Donlon was serving as the commanding officer of the U.S. Army Special Forces Detachment A-726 at Camp Nam Dong when a reinforced Viet Cong battalion suddenly launched a full-scale, predawn attack on the camp. During the violent battle that ensued, lasting 5 hours and resulting in heavy casualties on both sides, Capt. Donlon directed the defense operations in the midst of an enemy barrage of mortar shells, falling grenades, and extremely heavy gunfire. Upon the initial onslaught, he swiftly marshaled his forces and ordered the removal of the needed ammunition from a blazing building. He then dashed through a hail of small arms and exploding hand grenades to abort a breach of the main gate. En route to this position he detected an enemy demolition team of 3 in the proximity of the main gate and quickly annihilated them. Although exposed to the intense grenade attack, he then succeeded in reaching a 60mm mortar position despite sustaining a severe stomach wound as he was within 5 yards of the gun pit. When he discovered that most of the men in this gunpit were also wounded, he completely disregarded his own injury, directed their withdrawal to a location 30 meters away, and again risked his life by remaining behind and covering the movement with the utmost effectiveness. Noticing that his team sergeant was unable to evacuate the gun pit he crawled toward him and, while dragging the fallen soldier out of the gunpit, an enemy mortar exploded and inflicted a wound in Capt. Donlon’s left shoulder. Although suffering from multiple wounds, he carried the abandoned 60mm mortar weapon to a new location 30 meters away where he found 3 wounded defenders. After administering first aid and encouragement to these men, he left the weapon with them, headed toward another position, and retrieved a 57mm recoilless rifle. Then with great courage and coolness under fire, he returned to the abandoned gun pit, evacuated ammunition for the 2 weapons, and while crawling and dragging the urgently needed ammunition, received a third wound on his leg by an enemy hand grenade. Despite his critical physical condition, he again crawled 175 meters to an 81mm mortar position and directed firing operations which protected the seriously threatened east sector of the camp. He then moved to an eastern 60mm mortar position and upon determining that the vicious enemy assault had weakened, crawled back to the gun pit with the 60mm mortar, set it up for defensive operations, and turned it over to 2 defenders with minor wounds. Without hesitation, he left this sheltered position, and moved from position to position around the beleaguered perimeter while hurling hand grenades at the enemy and inspiring his men to superhuman effort. As he bravely continued to move around the perimeter, a mortar shell exploded, wounding him in the face and body. As the long awaited daylight brought defeat to the enemy forces and their retreat back to the jungle leaving behind 54 of their dead, many weapons, and grenades, Capt. Donlon immediately reorganized his defenses and administered first aid to the wounded. His dynamic leadership, fortitude, and valiant efforts inspired not only the American personnel but the friendly Vietnamese defenders as well and resulted in the successful defense of the camp. Capt. Donlon’s extraordinary heroism, at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty are in the highest traditions of the U.S. Army and reflect great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of his country.

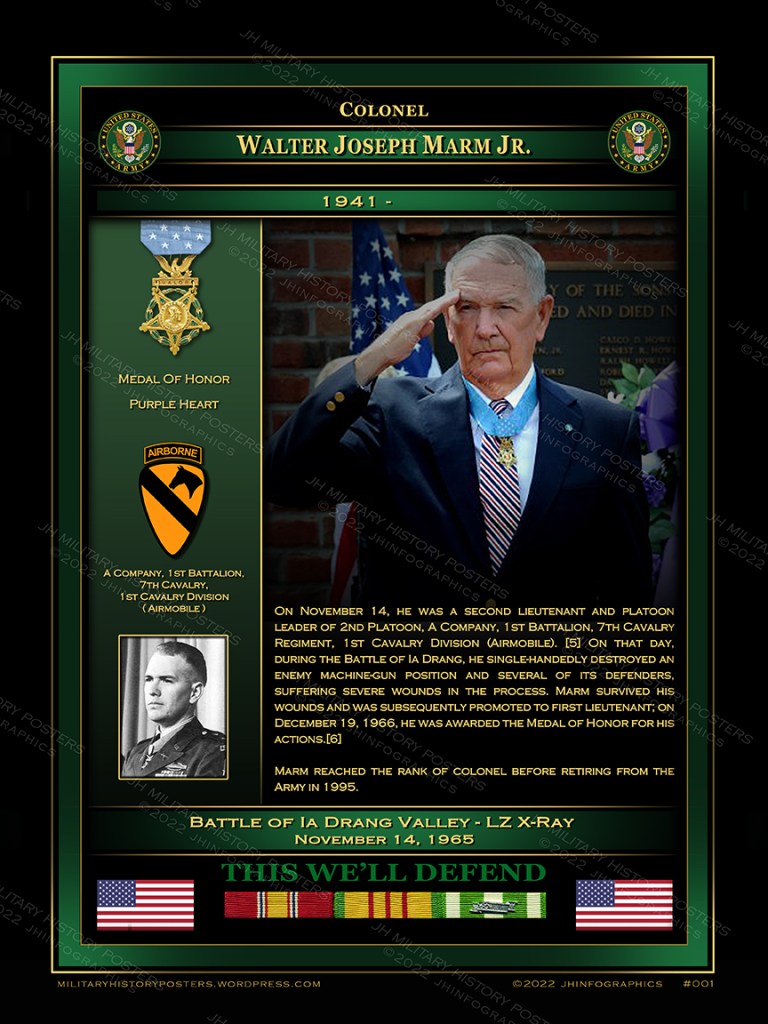

COLONEL WALTER JOSEPH MARM, JR.

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty. As a platoon leader in the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), 1st Lt. Marm demonstrated indomitable courage during a combat operation. His company was moving through the valley to relieve a friendly unit surrounded by an enemy force of estimated regimental size. 1st Lt. Marm led his platoon through withering fire until they were finally forced to take cover. Realizing that his platoon could not hold very long, and seeing four enemy soldiers moving into his position, he moved quickly under heavy fire and annihilated all 4. Then, seeing that his platoon was receiving intense fire from a concealed machine gun, he deliberately exposed himself to draw its fire. Thus locating its position, he attempted to destroy it with an antitank weapon. Although he inflicted casualties, the weapon did not silence the enemy fire. Quickly, disregarding the intense fire directed on him and his platoon, he charged 30 meters across open ground, and hurled grenades into the enemy position, killing some of the 8 insurgents manning it. Although severely wounded, when his grenades were expended, armed with only a rifle, he continued the momentum of his assault on the position and killed the remainder of the enemy. 1st Lt. Marm’s selfless actions reduced the fire on his platoon, broke the enemy assault, and rallied his unit to continue toward the accomplishment of this mission. 1st Lt. Marm’s gallantry on the battlefield and his extraordinary intrepidity at the risk of his life are in the highest traditions of the U.S. Army and reflect great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of his country.

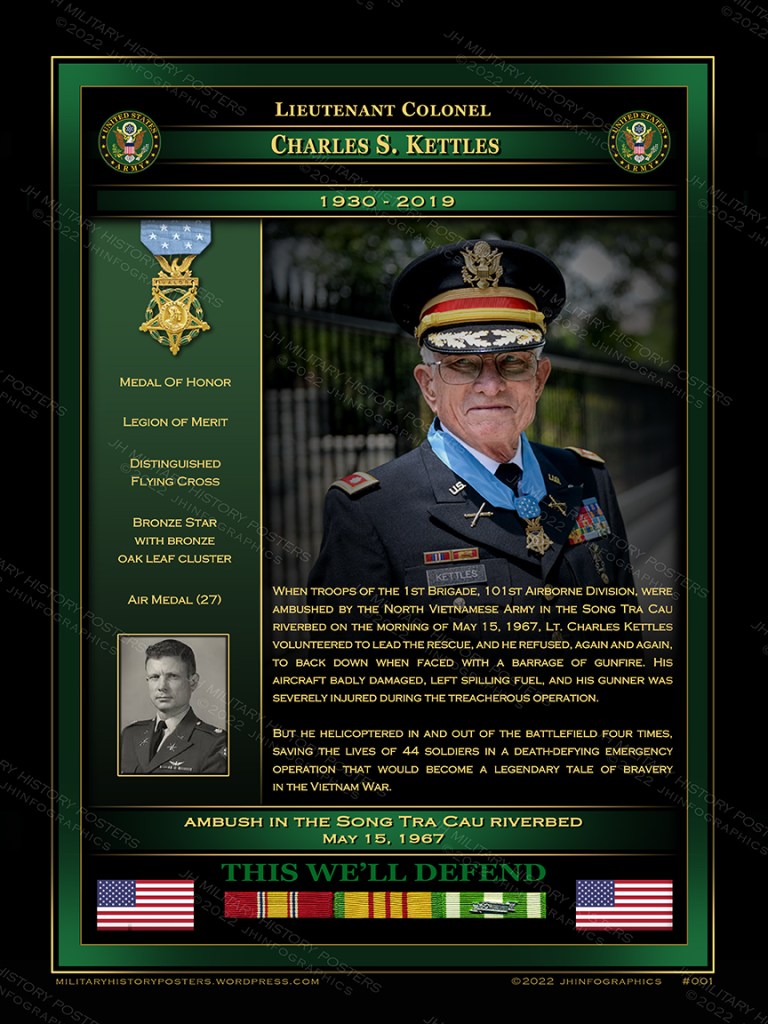

LIEUTENANT COLONEL CHARLES S. KETTLES

On May 15, 1967, personnel of the 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, were ambushed in the Song Tra Cau riverbed by an estimated battalion-sized force of People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) regulars with numerous automatic weapons, machine guns, mortars, and recoilless rifles. The PAVN fired from a fortified complex of deeply embedded tunnels and bunkers, and was shielded from suppressive fire. Upon hearing that the 1st Brigade had suffered casualties during an intense firefight with the enemy, then-Major Kettles volunteered to lead a flight of six UH-1D helicopters to bring reinforcements to the embattled force and to evacuate wounded personnel. As the flight approached the landing zone, it came under heavy fire from multiple directions and soldiers were hit and killed before they could dismount the arriving helicopters.

Small arms and automatic weapons fire continued to rake the landing zone, inflicting heavy damage to the helicopters and soldiers. Kettles, however, refused to depart until all reinforcements and supplies were off-loaded and wounded personnel were loaded on the helicopters to capacity. Kettles then led the flight out of the battle area and back to the staging area to pick up additional reinforcements.

With full knowledge of the intense fire awaiting his arrival, Kettles returned to the battlefield. Bringing additional reinforcements, he landed in the midst of mortar and automatic weapons fire that seriously wounded his gunner and severely damaged his aircraft. Upon departing, Kettles was advised by another helicopter crew that he had fuel streaming out of his aircraft. Despite the risk posed by the leaking fuel, he nursed the damaged aircraft back to base.

Later that day, the infantry battalion commander requested immediate, emergency extraction of the remaining 40 troops as well as four members of Kettles’ unit who had become stranded when their helicopter was shot down. With only one flyable UH-1 helicopter remaining in his company, Kettles volunteered to return to the landing zone for a third time, leading a flight of six evacuation helicopters, five of which were from the 161st Aviation Company. During the extraction, Kettles was informed by the last helicopter that all personnel were on board, and departed the landing zone accordingly. Army gunships supporting the evacuation also departed the area.

While returning to base, Kettles was advised that eight troops had been unable to reach the evacuation helicopters due to the intense fire. With complete disregard for his own safety, Kettles passed the lead to another helicopter and returned to the landing zone to rescue the remaining troops. Without gunship, artillery, or tactical aircraft support, the PAVN concentrated all firepower on his lone aircraft, which was immediately hit by a mortar round that damaged the tail boom and a main rotor blade and shattered both front windshields and the chin bubble. His aircraft was further raked by small arms and machine gun fire.

Despite the intense fire, Kettles maintained control of the aircraft and situation, allowing time for the remaining eight soldiers to board the aircraft. In spite of the severe damage to his helicopter, Kettles once more skillfully guided his heavily damaged aircraft to safety. Without his courageous actions and superior flying skills, the last group of soldiers and his crew would never have made it off the battlefield.

In 1968, Kettles received the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) for these actions, and on July 18, 2016, following a special Act of Congress to extend the time limit for awarding the Medal of Honor (for this particular case only), his DSC was upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

A soldier who was there that day said “Maj. Kettles became our John Wayne,” Obama said, adding his own take: “With all due respect to John Wayne, he couldn’t do what Chuck Kettles did.”

MAJOR GENERAL PATRICK H. BRADY

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty, Maj. BRADY distinguished himself while serving in the Republic of Vietnam commanding a UH-1H ambulance helicopter, volunteered to rescue wounded men from a site in enemy held territory which was reported to be heavily defended and to be blanketed by fog. To reach the site he descended through heavy fog and smoke and hovered slowly along a valley trail, turning his ship sideward to blow away the fog with the backwash from his rotor blades. Despite the unchallenged, close-range enemy fire, he found the dangerously small site, where he successfully landed and evacuated 2 badly wounded South Vietnamese soldiers. He was then called to another area completely covered by dense fog where American casualties lay only 50 meters from the enemy. Two aircraft had previously been shot down and others had made unsuccessful attempts to reach this site earlier in the day. With unmatched skill and extraordinary courage, Maj. BRADY made 4 flights to this embattled landing zone and successfully rescued all the wounded. On his third mission of the day Maj. Brady once again landed at a site surrounded by the enemy. The friendly ground force, pinned down by enemy fire, had been unable to reach and secure the landing zone. Although his aircraft had been badly damaged and his controls partially shot away during his initial entry into this area, he returned minutes later and rescued the remaining injured. Shortly thereafter, obtaining a replacement aircraft, Maj. BRADY was requested to land in an enemy minefield where a platoon of American soldiers was trapped. A mine detonated near his helicopter, wounding 2 crew members and damaging his ship. In spite of this, he managed to fly 6 severely injured patients to medical aid. Throughout that day Maj. BRADY utilized 3 helicopters to evacuate a total of 51 seriously wounded men, many of whom would have perished without prompt medical treatment. Maj. BRADY’S bravery was in the highest traditions of the military service and reflects great credit upon himself and the U.S. Army.

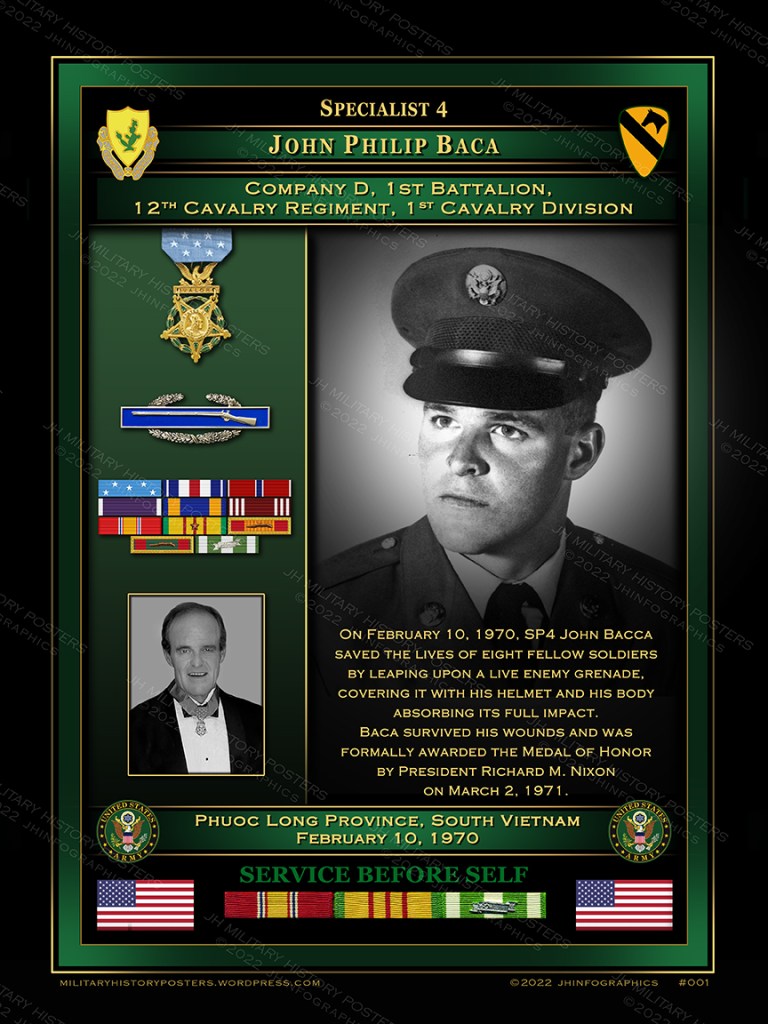

SPECIALIST 4 JOHN PHILIP BACA

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. Sp4c. Baca, Company D, distinguished himself while serving on a recoilless rifle team during a night ambush mission. A platoon from his company was sent to investigate the detonation of an automatic ambush device forward of his unit’s main position and soon came under intense enemy fire from concealed positions along the trail. Hearing the heavy firing from the platoon position and realizing that his recoilless rifle team could assist the members of the besieged patrol, Sp4c. Baca led his team through the hail of enemy fire to a firing position within the patrol’s defensive perimeter. As they prepared to engage the enemy, a fragmentation grenade was thrown into the midst of the patrol. Fully aware of the danger to his comrades, Sp4c. Baca unhesitatingly, and with complete disregard for his own safety, covered the grenade with his steel helmet and fell on it as the grenade exploded, thereby absorbing the lethal fragments and concussion with his body. His gallant action and total disregard for his personal well-being directly saved 8 men from certain serious injury or death. The extraordinary courage and selflessness displayed by Sp4c. Baca, at the risk of his life, are in the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit on him, his unit, and the U.S. Army.