MASTER SERGEANT ROY BENAVIDEZ

On May 2, 1968, a 12-man Special Forces patrol, which included nine Montagnard tribesmen, was surrounded by an NVA infantry battalion of about 1,000 men. Benavidez heard the radio appeal for help and boarded a helicopter to respond. Armed only with a knife, he jumped from the helicopter carrying his medical bag and ran to help the trapped patrol. Benavidez “distinguished himself by a series of daring and extremely valorous actions… and because of his gallant choice to join voluntarily his comrades who were in critical straits, to expose himself constantly to withering enemy fire, and his refusal to be stopped despite numerous severe wounds, saved the lives of at least eight men.”

At one point in the battle an NVA soldier accosted him and stabbed him with his bayonet. Benavidez pulled it out, drew his own knife, killed him and kept going, leaving his knife in the NVA soldier’s body. He later killed two more NVA soldiers with an AK-47 while providing cover fire for the people boarding the helicopter. After the battle, he was evacuated to the base camp, examined, and thought to be dead. As he was placed in a body bag among the other dead in body bags, he was suddenly recognized by a friend who called for help. A doctor came and examined him but believed Benavidez was dead. The doctor was about to zip up the body bag when Benavidez managed to spit in his face, alerting the doctor that he was alive. Benavidez had a total of 37 separate bullet, bayonet, and shrapnel wounds from the six-hour fight with the enemy battalion.

Benavidez was evacuated once again to Fort Sam Houston’s Brooke Army Medical Center, where he eventually recovered. He received the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism and four Purple Hearts. In 1969, he was assigned to Fort Riley, Kansas. In 1972, he was assigned to Fort Sam Houston, Texas where he remained until retirement.

COMMAND SERGEANT MAJOR BENNIE G. ADKINS

CSM Adkins was deployed to Vietnam for three non-consecutive tours while in the Special Forces: the first was for six months, beginning in February 1963. The second tour started in September 1965 and lasted for a year. The last one was from January 1971 until December that same year.

His second tour in Vietnam was when the most remarkable actions would happen. On March 9, 1966, then-Sergeant First Class Bennie Adkins was at Camp A Shau, serving as an Intelligence Sergeant with Detachment A-102, 5th Special Forces Group, 1st Special Forces. Their early morning hours were welcomed by a large force of North Vietnamese soldiers attacking them. Sergeant Adkins did not waste a second and rushed amidst the hail of enemy fire to man a mortar position to defend the camp. The enemy mortars hit him on a few occasions, and he incurred wounds from them. But Adkins was undeterred. He continued fighting. When he heard that several soldiers were wounded, he left his position and had another soldier man it so he could run through the mortar rounds and onto his wounded comrades’ position. Without hesitation, he dragged several of them to safety. When the hostilities subsided, Adkins exposed himself to the enemy snipers so he could carry the wounded soldiers to a safer area.

He exposed himself to enemy bullets even more while transporting a wounded man to an airstrip, and if all these were not enough yet, members of the Civilian Irregular Defense Group who had defected to fight with the Viet Cong began firing at them, too, with their heavy small arms. When a resupply air drop landed outside of the camp perimeter, Sergeant First Class Adkins, again, moved outside of the camp walls to retrieve the much needed supplies. During the early morning hours of March 10, 1966 enemy forces launched their main attack and within two hours, Sergeant First Class Adkins was the only man firing a mortar weapon. When all mortar rounds were expended, Sergeant First Class Adkins began placing effective recoilless rifle fire upon enemy positions.

Despite receiving additional wounds from enemy rounds exploding on his position, Sergeant First Class Adkins fought off intense waves of attacking Viet Cong. Sergeant First Class Adkins eliminated numerous insurgents with small arms fire after withdrawing to a communications bunker with several soldiers. Running extremely low on ammunition, he returned to the mortar pit, gathered vital ammunition and ran through intense fire back to the bunker. After being ordered to evacuate the camp, Sergeant First Class Adkins and a small group of soldiers destroyed all signal equipment and classified documents, dug their way out of the rear of the bunker and fought their way out of the camp. While carrying a wounded soldier to the extraction point he learned that the last helicopter had already departed. Sergeant First Class Adkins led the group while evading the enemy until they were rescued by helicopter on March 12, 1966.

SERGEANT MAJOR JOHN L. CANLEY

The crackling barrage of incoming enemy gunfire pinned down three U.S. Marines that lay wounded in the mud, screaming for help and medical attention.

It was 1968 and the Tet Offensive was raging as American forces moved to retake Huế city, located in central Vietnam on the banks of the Perfume River. Ten thousand North Vietnamese and Vietcong troops seized the heart of the city, turning houses and streets into bunkered positions. South Vietnamese and U.S. forces were unprepared for the large-scale assault that forced the Marines into the first major urban combat the United States had seen since the Korean War.

Marines nearby attempted to rescue their wounded brothers, but the barrage of bullets and rocket-propelled grenades kept them from advancing toward them—that was, until “Gunny” walked in.

“So they hear a noise and they look back and there’s Canley. He’s walking down, upright, not running, walks over the little berm, picks up the first guy, throws him over his shoulder and walks back,” John Ligato, a former Marine and FBI agent told Newsweek. “So there’s two independent eyewitnesses on this…Canley says to them, individually, ‘keep down there’s a lot of incoming.'”

Retired Marine Sergeant Major John Canley, who at the time was serving as the company gunnery sergeant for Alpha Company First Battalion, First Marine Regiment, dropped the wounded Marine on his shoulder behind a covered position, turned, and walked back to grab the second injured Marine—dropping him off only to return and retrieve the third Marine. “He never ran and he never ducked,” said Ligato, chuckling at how calm Canley could be as rounds whizzed past him. “You know, it’s just amazing. I don’t know if he had some sort of death wish or what—Gunny says that he just gets into a zone and does what he has to do…I don’t know how the bullets didn’t hit him.”

Canley is credited with saving scores of his fellow Marines between January 31 and February 6, 1968, as he assumed command of the Marines after the company commander was seriously wounded. His heroics came despite sustaining injuries in two separate battles over the course of a week, which earned him the Purple Heart.

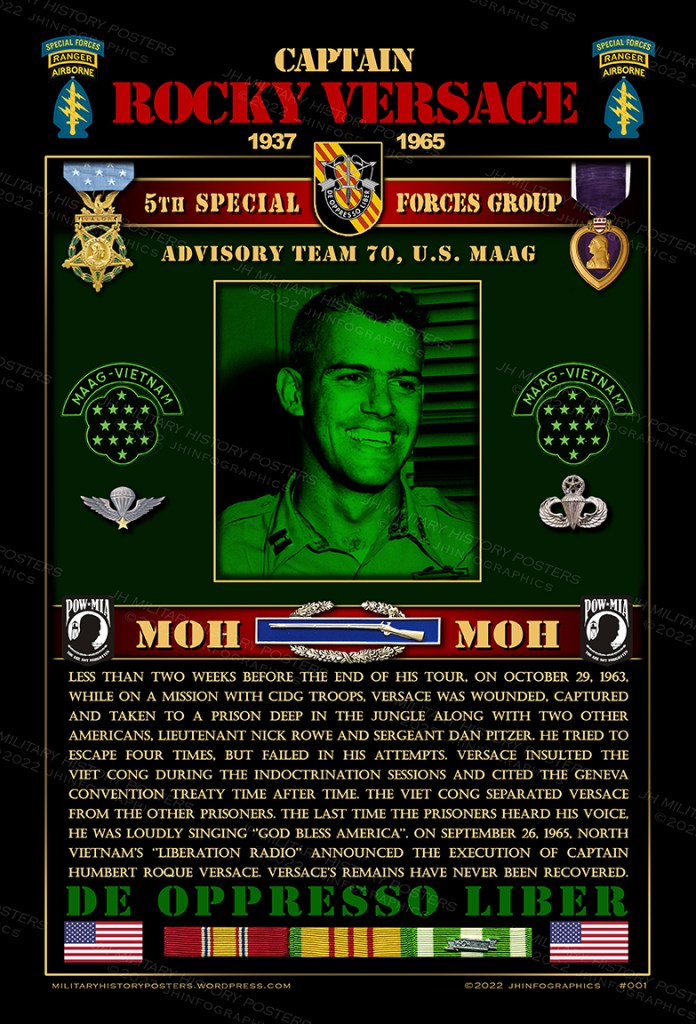

CAPTAIN HUMBERT ROQUE VERSACE

Following the completion of his initial 12-month tour, CPT Versace extended his tour in May 1963 for an additional six months, and was assigned to Advisory Team 70 as Intelligence Advisor to Civil Defense and Self Defense Forces operating in An Xuyen Province (IV Corps Tactical Zone) in the Mekong Delta Region of South Vietnam. It was in this assignment that CPT Versace was wounded and captured with two other Special Forces soldiers (SFC Pitzer and 1LT Nick Rowe [HoF 1989]) on 29 October 1963, while on an operation with Special Forces Team A-23, at Tan Phu on the edge of the U Minh Forest.

Upon arrival in the Viet Cong jungle prison camp, CPT Versace assumed command as senior prisoner to represent his fellow Americans. He was immediately labeled a troublemaker by his captors for insisting that they honor the Geneva Convention’s protections for captured prisoners of war. The Viet Cong did not acknowledge any protections guaranteed to prisoners as required by the Geneva Convention, and considered the three Americans to be “war criminals.” Soon he was separated fromRowe and Pitzer and put in a bamboo isolation cage six feet long, two feet wide, and three feet high. According to Rowe and Pitzer, “He was kept in irons, flat on his back, it was dark and hot [from thatch on the roof and outside bamboo walls], and they only let him out to use that latrine and to eat. What they were trying to do was to break him. They even offered better food and they would let him out if he would cooperate, but he would not. They wanted to get him to (1) quit arguing with them and (2) accept their propaganda. The Vietnamese gave him the word that they knew he was an S2 advisor.”

According to SFC Pitzer, “Rocky walked his own path. All of us did but for that guy, duty, honor, country was a way of life. He was the finest example of an officer I have known. To him it was a matter of liberty or death, the big four [name, rank, service number, and date of birth] and nothing more. There was no other way for him.

Once, Rocky told our captors that as long as he was true to God and true to himself, what was waiting for him after this life was far better than anything that could happen now. So he told them that they might as well kill him then and there if the price of his life was getting more from him than name, rank, and serial number”. Pitzer also noted that “The VC realized Rocky was a Captain, Nick [Rowe] a Lieutenant, and I a Sergeant, so they singled him out as ranking man. Rocky stood toe to toe with them. He told them to go to hell in Vietnamese, French, and English. He got a lot of pressure and torture, but he held his path. As a West Point grad, it was duty, honor, country. There was no other way…I know that he valued that one moment of honor more than he would have a lifetime of compromises.”

CPT Versace was soon ordered to be kept in an isolation hut with thatch on the roof and sides, which made mid-day temperatures inside as hot as an oven. The Department of Defense Prisoner and Missing Personnel Office (DPMO) stated that: “…CPT Versace demonstrated exceptional leadership by communicating positively to his fellow prisoners. He lifted morale when he passed messages by singing them into the popular songs of the day. When he used his Vietnamese language skills to protest improper treatment to the guards, CPT Versace was again put into leg irons and gagged. Unyielding, he steadfastly continued to berate the guards for their inhuman treatment.

The Communist guards simply elected harsher treatment by placing him in an isolation box, to put him out of earshot and to keep him away from the other US POWs for the remainder of his stay in camp. However, CPT Versace continued to leave notes in the latrine for his fellow inmates, and continued to sing even louder.”

He took advantage of the first opportunity to escape when he attempted to drag himself on his hands and knees out of the camp through dense swamp and forbidding vegetation to freedom. The guards quickly discovered him outside the camp and recaptured him. After recapture, Versace was returned to leg irons and his wounds were left untreated.

He was placed on a starvation diet of rice and salt. During this period Viet Cong guards told other US prisoners in the camp that despite beatings, CPT Versace refused to give in. On one occasion a guard attempted to coerce him to cooperate by twisting the wounded and infected leg, to no avail.

Versace and the other US Army prisoners were frequently moved from one prisoner of war camp to another. Versace was often moved individually without benefit of being near his fellow prisoners. BG John Nicholson participated in the numerous operations launched to free Versace and his fellow prisoners. According to BG Nicholson and others, villagers reported that CPT Versace was paraded through the hamlets with a rope around his neck, hands tied, bare footed, head swollen and yellow in color, with hair turned white.

The villagers stated that he not only resisted the Viet Cong attempts to get him to admit war crimes and aggression, but also would verbally and convincingly counter their assertions in a loud voice so that the villagers could hear. The local rice farmers were surprised at Versace’s strength of character and his unwavering commitment to his God and the United States.

CPT Versace was a prisoner of the Viet Cong until 26 September 1965, when he was executed by his captors because of his tenacious resistance and rigid adherence to the Code of Conduct. He was awarded a posthumous Purple Heart on 2 July 1966 and a posthumous Silver Star on 19 May 1971. US Army Special Operations Command resubmitted his Medal of Honor nomination and CPT Versace was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor on 8 July 2002. Additionally he was awarded the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal, National Defense Service Medal, Ranger Tab, Parachutist Badge, Expert Infantry Badge and the Combat Infantry Badge. CPT Versace was inducted posthumously into the Hall of Fame in 2003.

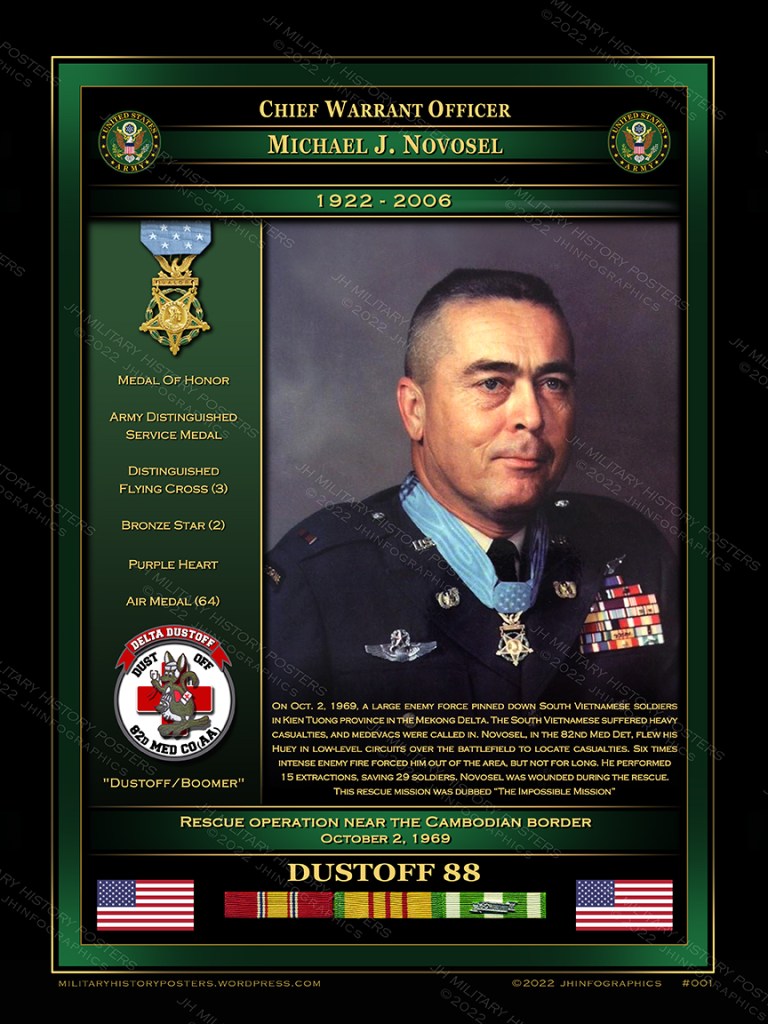

CHIEF WARRANT OFFICER MICHAEL J. NOVOSEL

On Oct. 2, 1969, a large enemy force pinned down South Vietnamese soldiers in Kien Tuong province in the Mekong Delta. The South Vietnamese suffered heavy casualties, and medevacs were called in. Novosel, in the 82nd Medical Detachment, flew his Huey in low-level circuits over the battlefield to locate casualties. Six times intense enemy fire forced him out of the area, but not for long. He performed 15 extractions, saving 29 soldiers. On one flight, Novosel hovered his helicopter backward into enemy fire to reach a wounded fighter and held his position while the man was pulled aboard. Novosel was wounded during the rescue.

Two months later, a new pilot arriving in Vietnam requested assignment to the 82nd Medical Detachment. He was Warrant Officer Michael J. Novosel Jr. A month before the father was to return home, the son’s helicopter came under fire, and Novosel Jr. made an emergency landing. Novosel Sr., with wounded aboard his helicopter, dropped down to pick up his son and the grounded dustoff crew. One week later, Novosel Sr. and his helicopter were grounded. He recognized the pilot coming to the rescue him—it was his son. “I’ll never hear the last of this,” Novosel recalled saying.

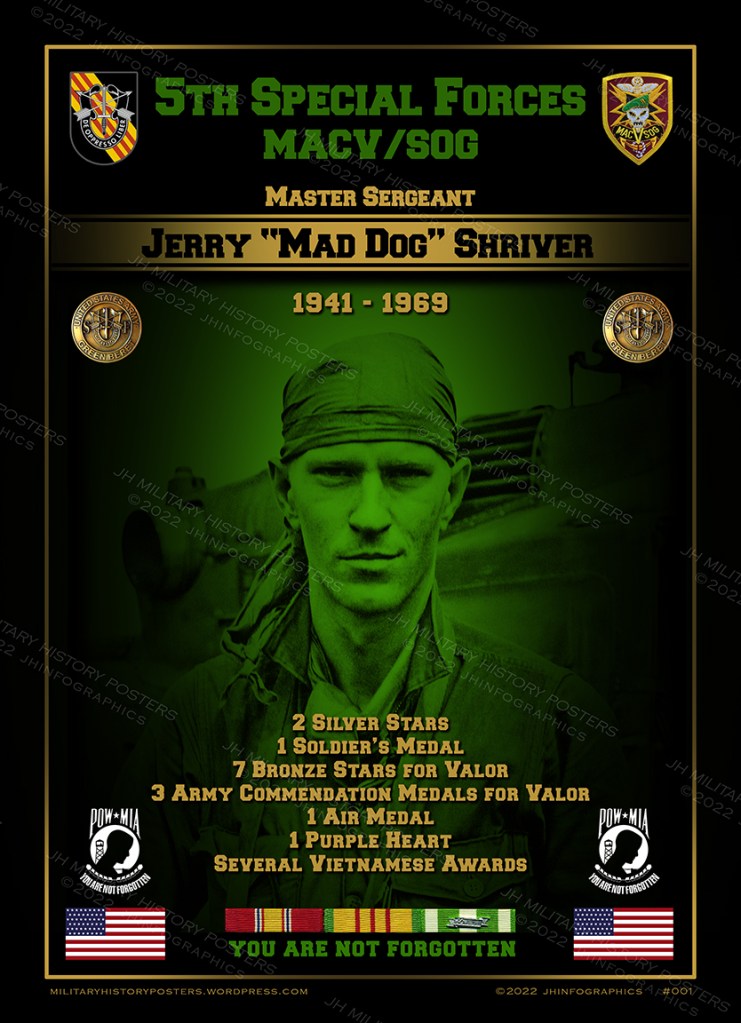

MASTER SERGEANT JERRY “MAD DOG” SHRIVER

Because of the secretive nature of their mission, Shriver’s unit was denied most of their Aerial assets by the US State Department. Right before he got into his chopper Shriver turned to his friend who was seeing him off and said “Take care of my boy” referring to Klaus. As the SOG raider unit took off, the first helicopter was turned around because of mechanical problems, so Shriver’s 1st platoon and 2nd platoon continued on alone.

As soon as they landed, they were subjected to vicious arcs of emplaced machine gun fire. Overlapping fields of fire from heavily reinforced concrete bunkers stitched across the LZ. From the back of the LZ, Mad Dog Shriver radioed that a machine gun bunker to his left-front had his men pinned and asked if anyone could suppress it to relieve the pressure. Taking shelter in a crater, Capt. Cahill, 1st Lt. Marcantel and a medic, Sergeant Ernest Jamison, radioed that they were pinned, too. Then Jamison dashed out to retrieve a wounded man. Tragically, he was targeted by machine gun fire and killed.

No one else could engage the machine gun that trapped COSVN Raiders. It was up to Mad Dog and his Montagnards. Shriver radioed that he was going to try and flank the MG positions. His half-smirk steeled the resolve of his fighting Montagnards. Then they were on their feet charging. Shriver was his old self again, fear replaced by confidence. He aggressively moved to enemy gunfire, 5 of his handpicked mountain men running with him as they dashed through the flying bullets, into the treeline, into the very mouth of the COSVN.

Mad Dog Shriver was never seen again. At the other end of the LZ, the battle raged on. Sergeant Jamison’s body lay just past where Capt. Cahill and 1LT Marcantel took shelter from a torrent of MG fire. When Cahill lifted his head, a round hit him in the mouth, deflected up and blinded him in his right eye and left him unconscious and bleeding from his wounds. In a nearby crater, 2nd Platoon’s Lt. Greg Harrigan directed helicopter gunships who’s rockets and mini-guns were trying to suppress the aggressive NVA. Harrigan reported, more than half his platoon were killed or wounded.

For 45 minutes the Green Beret lieutenant kept the enemy at bay with accurate gun run requests before he too was hit and killed. Hours dragged by. Wounded men laid untreated, bleeding out in the sun. Several times, the Hueys tried to MEDEVAC their wounded but each time heavy fire drove them off. Finally a passing Australian twin-jet bomber from No. 2 Squadron at Phan Rang heard the SOG Raider Company’s desperate calls for help on the emergency radio frequency, and broke off from it’s flight plan. Ignoring the fact that the request came from within the supposedly “neutral” Cambodian border, the Australian crew dropped a payload on the enemy positions. By that point, only 1LT Marcantel was still directing calls for CAS, eventually calling in danger close missions so close that they wounded himself and his surviving nine Montagnards. After 8 hours of intense battle, three Hueys raced in. Of the 18 members of the Hatchet platoon, two were confirmed dead, ten were wounded and six, including Shriver, were listed as MIA.

FIRST SERGEANT JIMMIE EARL HOWARD

On the evening of June 13, 1966, Howard and his platoon of 15 Marines along with two Navy corpsmen were dropped behind enemy lines atop Hill 488. The mission of this reconnaissance unit was to observe enemy troop movements in the valley and call in air and artillery strikes. Within days, the enemy descended on them in force; on the night of June 15, 1966, a full battalion of Viet Cong (over 300 men) engaged the squad of 18. After receiving severe wounds from an enemy grenade, Howard distributed ammunition to his men and directed air strikes on the enemy.

By dawn, his beleaguered platoon still held their position. During the 12 hours of combat, 200 enemy troops were killed as against the loss of six American lives.

In addition to receiving the Medal of Honor for his actions on Hill 488, Howard received a gold star in lieu of a third

Purple Heart for wounds received on June 16, 1966. Members of Howard’s platoon were decorated for their actions in this fight with four Navy Crosses and thirteen Silver Stars.