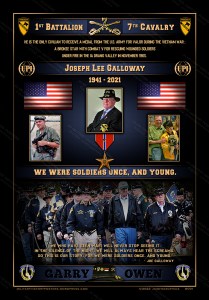

From a Washington Post obit by Harrison Smith headlined “Joseph Galloway, chronicler and champion of soldiers in Vietnam, dies at 79”:

In November 1965, journalist Joseph L. Galloway hitched a ride on an Army helicopter flying to the Ia Drang Valley, a rugged landscape of red dirt, brown elephant grass and truck-size termite mounds in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam. Stepping off the chopper, he arrived at a battlefield that one Army pilot later called “hell on Earth, for a short period of time.”

Mr. Galloway, a 24-year-old reporter for United Press International, went on to witness and participate in the first major battle of the Vietnam War, in which an outmanned American battalion fought off three North Vietnamese army regiments while taking heavy casualties. He carried an M16 rifle alongside his notebook and cameras, and in the heat of battle, he charged into the fray to pull an Army private out of the flames of a napalm blast.

“At that time and that place, he was a soldier,” Maj. Gen. Joseph K. Kellogg said more than three decades later, when the Army awarded Mr. Galloway the Bronze Star Medal for his efforts to save the private. “He was a soldier in spirit, he was a soldier in actions and he was a soldier in deeds.”

Mr. Galloway later recounted the battle in a best-selling book, “We Were Soldiers Once . . . and Young,” written with retired Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore, the U.S. battalion commander at Ia Drang. The book was adapted into the movie “We Were Soldiers” starring Mel Gibson as Moore and Barry Pepper as Mr. Galloway, and was acclaimed for its unflinching account of one of the war’s bloodiest battles.

“What I saw and wrote about broke my heart a thousand times, but it also gave me the best and most loyal friends of my life,” Mr. Galloway said in an interview with the Victoria Advocate, the Texas daily where he had once worked as a cub reporter. “The soldiers accepted me as one of them, and I can think of no higher honor.”

Mr. Galloway, whose reporting took him from the jungles of Vietnam to the halls of the Kremlin and the deserts of Iraq, was 79 when he died Aug. 18 at a hospital in Concord, N.C….

In a journalism career that spanned nearly five decades, Mr. Galloway became known for writing elegant, richly detailed stories that immersed readers in conflicts around the world, including the 1971 war between India and Pakistan and the 1991 Persian Gulf War, which he covered while embedded with a tank unit for U.S. News & World Report.

A native Texan who grew up reading the collected reporting of Ernie Pyle, who told the story of World War II through the eyes of ordinary GIs, Mr. Galloway exalted the bravery of American soldiers even as he questioned the wisdom of the leaders who sent them into battle. Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf, who led U.S. forces during the Gulf War, once called him “the finest combat correspondent of our generation — a soldiers’ reporter and a soldiers’ friend.”

Mr. Galloway spent 22 years with UPI and retired in 2010 after working as a military affairs correspondent and columnist for the newspaper chains Knight Ridder and McClatchy, where he wrote critically of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. He was played by Tommy Lee Jones in director Rob Reiner’s movie “Shock and Awe” about Knight Ridder’s skeptical coverage of the George W. Bush administration’s case for invading Iraq.

But he remained best known for his books and articles about Vietnam, most notably “We Were Soldiers Once . . . and Young,” which sold more than 1 million copies. He and Moore spent 10 years researching the volume, interviewing more than 250 people, including Vietnamese military commanders and U.S. veterans and their families.

“It is thoroughly researched, written with equal rations of pride and anguish, and it goes as far as any book yet written toward answering the hoary question of what combat is really like,” author and Vietnam War correspondent Nicholas Proffitt wrote in a review for the New York Times. He went on to call it “a car crash of a book; you are horrified by what you’re seeing, but you can’t take your eyes off it.”

The Battle of Ia Drang began Nov. 14, 1965, after Moore and some 450 soldiers from the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry were helicoptered to a clearing known as Landing Zone X-Ray. They were there on a search-and-destroy mission — “It’s probably gonna be a long, hot walk in the sun,” the brigade commander had told Mr. Galloway — and soon came under withering fire.

For the next three days, they struggled to fight off North Vietnamese regulars, sometimes in bloody hand-to-hand combat. Helicopter gunships, fighter-bombers and artillery fire helped turn the tide, although a replacement battalion was ambushed and nearly wiped out while marching to another clearing, Landing Zone Albany, in what Mr. Galloway and Moore described as “the most savage one-day battle of the Vietnam War.”

By the end of the fighting, more than 230 Americans and some 3,000 North Vietnamese were dead at Ia Drang. Both sides claimed victory: North Vietnamese leaders came away certain that they could outlast the Americans, while U.S. commander William Westmoreland was convinced that his troops “could bleed the enemy to death over the long haul,” as Mr. Galloway and Moore put it.

Mr. Galloway, who had arrived on the first night of the battle, said he planned for years to write a book with Moore but had put it off until 1980, when he was flipping channels and came across a Vietnam War sequence in the movie “More American Graffiti,” which brought back memories of Huey helicopters and deafening machine-gun fire.

“I found myself sitting in my chair, shaking like a leaf, with tears rolling down my cheeks at the sight and the memories,” he said in 2017. “I thought, you can run from it, and it will catch you and eat you — or you can face it. I picked up the phone the next morning and called General Moore at his home in Colorado. ‘Are you ready to start work on this book?’ He said, ‘I sure am.’ ”

Few memories of Ia Drang were more painful for Mr. Galloway than the death of Pfc. Jimmy Nakayama, one of two soldiers who were accidentally hit with napalm during a misplaced airstrike on the battle’s second day. Joined by an Army medic who was immediately shot and killed, Mr. Galloway raced toward enemy fire to pull Nakayama from the flames. The private was evacuated but died in a hospital two days later.

After the Pentagon reopened nominations for Vietnam battlefield honors, Mr. Galloway was awarded the Bronze Star Medal in 1998, becoming the fourth American journalist to receive the honor for bravery in the conflict.

“I accept it,” he said at the time, “in memory of the 70-plus reporters and photographers who were killed covering the Vietnam War, trying to tell the truth and keep the country free.”

Joseph Lee Galloway Jr. was born in Bryan, Tex., in 1941, three weeks before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. His father served in the Army during World War II — Mr. Galloway did not meet him until after the war had ended….

Mr. Galloway attended community college for six weeks before dropping out in 1959 to enlist in the Army, which he viewed as a ticket out of South Texas. His mother persuaded him to go into journalism instead, reminding him that as a boy he had written a weekly newspaper for their neighborhood, banging away at a 1912 Remington typewriter.

He joined UPI in 1961 as a reporter in Kansas City, Mo., and within two years he was bureau chief in Topeka, Kan., where he pestered the news agency’s senior editors to send him to Vietnam, sensing from dispatches by Neil Sheehan of UPI and David Halberstam of the Times that conflict there was escalating.

Mr. Galloway got his wish in April 1965, landing in South Vietnam a month after the first American combat troops arrived in the country. He remained there for 16 months and was later UPI bureau chief in Jakarta, the Indonesian capital, and in New Delhi, Singapore, Moscow and Los Angeles.

He later won a National Magazine Award at U.S. News & World Report, for a cover story about the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Ia Drang, and worked as a special consultant to Secretary of State Colin L. Powell before joining Knight Ridder in 2002.

Mr. Galloway’s wife of 29 years, the former Theresa Null, died in 1996. His second marriage — to Karen Metsker, whose father was killed at Ia Drang — ended in divorce, and in 2012 he married Grace Liem Lim Suan Tzu, who worked as a nurse’s helper during the Vietnam War….

Mr. Galloway partnered with Moore on another book, “We Are Soldiers Still” (2008), and teamed with Marvin J. Wolf to write “They Were Soldiers” (2020), about the postwar lives of Vietnam veterans. He also appeared in documentaries such as “The Vietnam War” (2017), directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick.

“You do this out of sense of obligation to those who died and those who lived — those especially,” he said in 1993. “Their battle had been forgotten. You just can’t turn your back on something like that, not if you’ve seen it with your own eyes.”